Introduction

Asthma is the most commonly diagnosed respiratory ailment among adults, impacting roughly 8% of the working adult population (Cartier and Sastre, 2011). In the United Kingdom (UK), an estimated 4.3 million adults are under treatment for asthma alone (Kaufman, 2012). Asthma’s impact on the quality of life extends to those afflicted by the condition and their families. Persistent asthma symptoms lead to significant morbidity, with inadequate management resulting in an elevated rate of hospital admissions (Rees, 2010). While morbidity due to asthma is substantial, there has been a decrease in mortality rates associated with asthma in recent decades.

Pathophysiology of Asthma

The literature widely acknowledges the absence of a definitive ‘gold standard’ definition for asthma (Kaufman, 2011). The World Health Organization (WHO) (2010) characterizes asthma as an inflammatory condition characterized by recurrent episodes of breathlessness and wheezing. These episodes vary in severity and frequency. Killeen and Skora (2013, p.11) offer an alternative definition, describing asthma as a “chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by three distinct responses: pulmonary inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway remodeling, triggered by various factors affecting only those predisposed to the disease.” Linzer (2007) simplifies asthma as recurring, reversible bronchospasms triggered by specific factors. Meanwhile, Busse et al. (2006) assert that asthma is a complex condition involving persistent airway obstruction, increased airway reactivity, and multifaceted inflammation.

Recruitment and activation of immune cells, including mast cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes, result in inflammation and cellular infiltration in the airways. Notably, Type 2 T-helper cells (Th2) are significant in initiating the immune cascade underlying inflammation, often leading to late asthmatic responses (Durham et al., 2000). This process releases various pre-formed and generated mediators, contributing to airway remodelling, characterized by extracellular protein deposition, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and increased goblet cell production (Holgate et al., 2000). These mechanisms render the airway epithelium fragile and denuded, thicken the epithelial sub-basement membranes, and result in heightened mucus production and viscosity, along with endothelial leakage causing mucosal swelling (Linzer, 2007). Furthermore, abnormalities in the parasympathetic and non-adrenergic non-cholinergic nervous systems, induced by mediators, can lead to heightened bronchial reactivity.

Figure 1: Mechanism of Allergen-Induced Late Asthmatic Response due to TH2-Type T-Lymphocyte Activation (reproduced with permission from Durham et al., 2000, p. S225).

Based on the pathophysiology elucidated earlier, asthma manifests through various clinical symptoms. These include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest constriction, coughing (often more pronounced at night), and fluctuating airflow obstruction (Kaufman, 2012).

Assessment and Diagnosis of Asthma

To confirm a potential diagnosis of asthma and rule out other possible conditions, it is crucial to conduct a systematic patient history assessment (Celli et al., 2004). There are several alternative diagnoses to consider when evaluating respiratory symptoms, including foreign body obstructions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary embolism (PE), pneumothorax, and cardiac issues (British Medical Journal, 2016). It’s important to note that the onset of respiratory symptoms beyond 40 tends to lean towards a COPD diagnosis rather than asthma (Tarasidis and Wilson, 2015).

To accurately determine the patient’s respiratory symptoms and exclude alternative diagnoses, it is imperative to gather the following information from the patient:

- Duration of Cough: Inquire about the length of time the patient has experienced a cough.

- Productive Cough: If the cough produces sputum, assess the thickness and colour of the sputum.

- Haemoptysis: Ask whether the patient has coughed up any blood.

- Allergies and Respiratory History: Investigate any history of allergies or other respiratory conditions.

- Family History: Check for a family history of asthma or other respiratory diseases.

- Other Medical Conditions: Identify any other diagnosed medical conditions the patient may have.

- Weight Loss: If applicable, inquire about recent weight loss and the amount.

- Occupational and Environmental Exposures: Determine if the patient has been exposed to any occupational or environmental factors.

- Smoking History: For patients with a smoking history:

- Determine if they have quit smoking.

- If not, ascertain the number of cigarettes smoked per day.

- If they have quit, gather details about the duration and intensity of their smoking habit and when they stopped.

- Medications: Ask whether the patient takes regular prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs.

This comprehensive patient history assessment is vital for thoroughly evaluating asthma and ensuring an accurate diagnosis while ruling out other potential conditions.

Before confirming a diagnosis of asthma, it is essential to conduct a thorough physical examination. This examination should follow a systematic approach, focusing primarily on the respiratory system (Baid, 2006; Moore, 2007). When necessary, clinical investigations should also be carried out. Spirometry, a widely available diagnostic tool, is the preferred method for identifying airflow obstruction. However, it requires proper training for reliable data collection and result interpretation. When conducted accurately, spirometry is the most effective means of detecting variable airflow obstruction and establishing a definitive asthma diagnosis (British Thoracic Society [BTS]/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN], 2016).

Spirometry measures two critical parameters: forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). These measurements help differentiate between obstructive and restrictive lung diseases. A positive diagnosis of asthma is indicated by airflow obstruction with reversibility (Bostock-Cox, 2010). Figure 2 below illustrates the diagnostic algorithm recommended by BTS/SIGN (2016) for confirming asthma diagnosis is shown in Figure 2 below.

Managing Asthma in Adult Patients

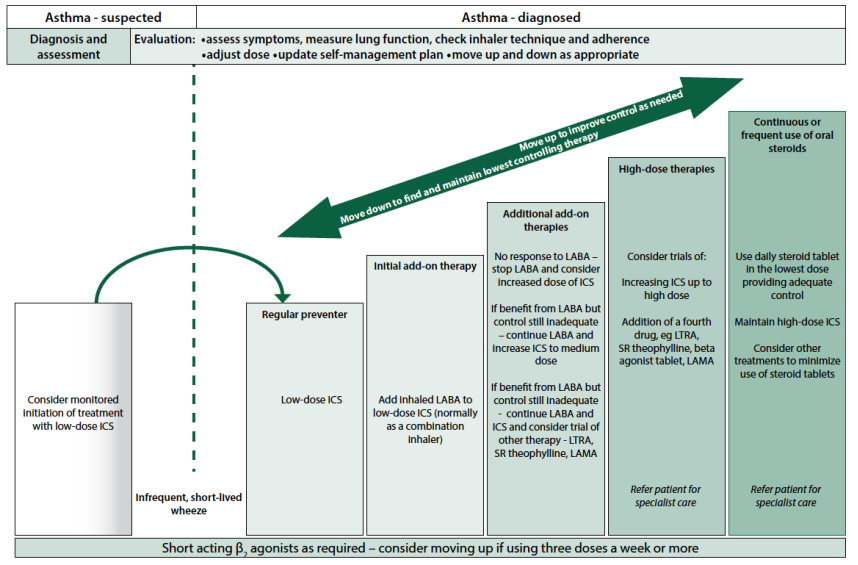

Asthma management in adult patients follows a stepwise approach based on the severity of their symptoms, as recommended by the BTS/SIGN (2016) guidelines in the “British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Please refer to Figure 3 below.

As depicted in Figure 3 above, a range of prescribed treatments is available for adults newly diagnosed with asthma. These treatments include beta2 agonists, muscarinic antagonists, and corticosteroids. Both beta2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists come in short-acting or long-acting forms. Short-acting beta2 agonists (SABA), such as Salbutamol and Terbutaline, and long-acting inhaled beta2 agonists (LABA), like Formoterol or Salmeterol, are examples of available options (British National Formulary [BNF], 2016a). For short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA), Ipratropium is a common choice, and the first-line long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) is Tiotropium (BNF, 2016b).

In newly diagnosed adults with mild to moderate asthma, treatment typically begins with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and a short-acting β-agonist (SABA) to alleviate and, if possible, prevent symptoms. According to BTS/SIGN (2016) guidelines, ICS drugs like beclomethasone or fluticasone are considered the most effective preventive medications for adult asthma. ICS inhalers act to reduce lung inflammation and irritation by mechanisms that involve the activation or suppression of specific genes related to the inflammatory process. However, it’s worth noting that the anti-inflammatory effects of ICS may take several hours to manifest due to the genomic processes involved (Horvath and Wanner, 2006). Therefore, a SABA for immediate symptom relief is also recommended (BTS/SIGN, 2016). Salbutamol is one such SABA that relaxes the smooth muscle cells in the airway walls by binding to the beta2 adrenoreceptor, stimulating the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), resulting in immediate symptom relief (Scullion and Holmes, 2010). If the patient’s condition doesn’t improve with these therapies, additional inhaled bronchodilators can be introduced stepwise, as illustrated in Figure 3.

In addition to pharmacological treatments, substantial evidence supports the idea that self-management education can improve health outcomes for individuals with asthma (BTS/SIGN, 2016). Self-management involves the tasks patients must undertake to cope with long-term conditions, including managing medical aspects, roles, and emotional aspects (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2004). In the context of asthma, self-management takes the form of personalized asthma action plans (PAAPs), which address the medical aspects of living with the condition and its broader challenges. According to Newell et al. (2015), individuals with asthma are four times more likely to experience a severe asthma attack requiring emergency hospital treatment if they lack a PAAP. PAAPs aim to empower asthma patients by:

- It is recognizing and avoiding known triggers whenever possible.

- Developing the skills to adjust treatments safely and effectively based on changing symptoms.

A well-implemented PAAP can help patients recognize when to seek medical or emergency care (Newell et al., 2015).